Challenging Cultural Dominance Continuums in Heritage Representation: Expanding the Narrative of a Native America in the Adirondack Park

Lia Maria Schifitto

Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of

M.A. in Sustainable Cultural Heritage

The American University of Rome

December 2017

The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his/her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others.

Lia Schifitto

Acknowledgements

To the mystical Adirondack Mountains, all who let me hear their stories, and to my loving family and friends for their support.

A special thank you to Curt Stager, Tim Messener, David Starbuck, Chuck Vandrei, Tom Lake, John Fadden, Don Stevens, Kay Olan, Roy Hurd, and Emily Pierini.

The supervisor of this thesis was Emily Pierini, PhD.

Word Count: 30,226

Abstract

This thesis tackles the often understudied issue of Western dominance in American heritage narratives. The case study is the Adirondack Park, located in Upstate New York and the largest public wilderness park in the United States. One of the first regions to designate land for environmental preservation, people living in the Adirondacks today and those who come to enjoy the space recreationally, feel passionately about Adirondack preservation efforts. The narrative, however, from which this identity in the landscape is formed, is based on roughly 200 years of history; missing from the general public’s knowledge and understanding of the region is thousands of years of Native American presence and influence. This thesis seeks to understand how American Indian culture is commonly misrepresented in American heritage narratives. The Adirondacks acts as a specific example of this in the texts, institutions, and general history readily available of the area. Furthermore, we must ask how this is shaping Americans’ perception of culture and the past. This thesis argues that increased representation, which brings environment into the Adirondacks’ cultural heritage, can act as one way to change the dialogue and increase a platform for Native American communities today. Such strides can aid in the preservation of their rich histories, traditions, and connections to the landscape.

Key Words: cultural landscape, heritage, representation, New York

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements…………………………………………………….3

Abstract………………………………………………………………...4

Table of Contents………………………………………………………5

List of Abbreviations…………………………………………………..7

List of Figures………………………………………………………….8

Chapter One:

Introduction …………………………………………………………...12

Chapter Two:

Literature Review: Discourse in Scholarly Sources…………………...21

1.1 Native American Invisibility in the Adirondacks……………………21

1.2 Stereotyping & Appropriation: The Noble Savage……………38

1.3 What is Heritage? Different Forms of Preservation…………54

Chapter Three:

Methodology……………………………………………………………66

Chapter Four:

Recognizing Native Heritage in the Adirondack Landscape

Analysis of Research Question One……………………………………75

Chapter Five:

Ending Western Cultural Heritage Dominance in the Adirondacks

Analysis of Research Question Two……………………………………99

Chapter Six:

Conclusion……………………………………………………………...119

Bibliography……………………………………………………………124

Appendix A: Case Books ……………………………………………...128

A.1 Casebook1: Camp Santanoni Participants…………………………….129

A. 2 Casebook 2: Individual Interviews……………………………….132

Appendix B: Interview Materials ………………………………………134

B.1 Interview Information Form……………………………………………135

B.2 Interview Consent Sheet…………………………………………. 136

B.3 Casebook 1 (Camp Santanoni) Interview Question Sheet……137

Appendix C: Interview Transcripts/Notes……………………………..138

C.1 Casebook 1……………………………………………………………139

C.2 Casebook 2………………………………………………………158

List of Abbreviations

1. DEC: Department of Environmental Conservation

2. UNESCO: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization

3. AIM: American Indian Movement

4. NAGPRA: Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act

5. CBC: Canadian Broadcasting Company

List of Figures

1. Maps

Fig. 1.1

Map of New York State, showing the location of the Adirondack Park …………………10

Fig. 1.2

Official DEC Map of the Adirondack Park………………………………………………11

2. Photographs

Fig. 2.1

Photograph of Great Camp Santanoni ……………………………………………………13

Fig. 2.2

Photograph of Great Camp Santanoni ……………………………………………………14

Fig. 2.3

Photograph of Santanoni Mountain………………………………………………………14

Fig. 2.4

Photograph of Boy Scout Indian Lore illustrations……………………………………….53

Fig.2.5

Photograph of Map Display of Adirondacks with markers

for archeological sites found (Adirondack Museum) …………………………………….89

Fig. 2.6

Photograph of Adirondack Museum on Blue Mountain Lake,

Peopled Wilderness Exhibit……………………………………………………………….90

Fig. 2.7

Photograph of Basket Weaving Display at Adirondack Museum…………………………90

Fig. 2.8

Photograph of Interviewing Camp Santanoni Tourists…………………………………….93

Fig. 2.9

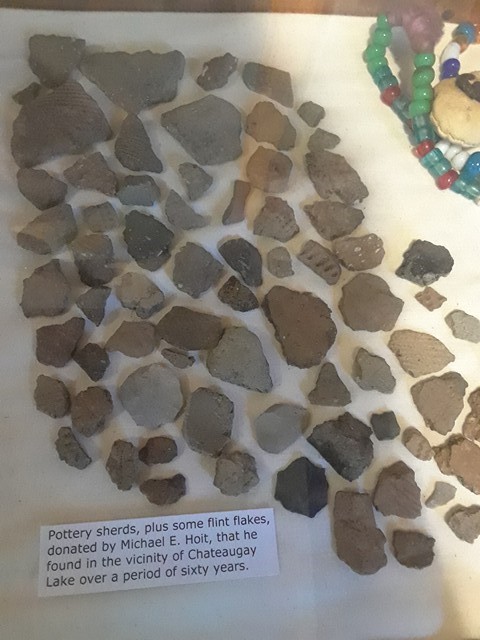

Photograph of Chateauguay Lake Pottery Shards at Six Nations Museum……………….110

Fig. 2.10

Photograph of Dugout Canoe found in Lake Placid at Six Nations Museum…………........110

Fig. 2.11

Photograph of Abenaki Heritage Festival Drum Circle……………………………...........112

Fig. 2.12

Photograph of Abenaki Heritage Festival Drum Circle……………………………….113

3. Diagrams

Fig. 3.1 Cultural Dominance Continuum ……………………………………………...120

Fig. 3.2 Age Range of Camp Santanoni Interviewees ………………………………...130

Fig. 3.3 Distance Traveled of Camp Santanoni Interviewees …………………………131

Maps for Reference

Fig.1.1

Map of New York State, showing the location of the Adirondack Park

http://www.flyfisherman.com/northeast/new-york/adirondack-park/

Fig.1.2

Official DEC Map of the Adirondack Park

http://www.dec.ny.gov/images/permits_ej_operations_images/adkmap16.jpg

Chapter One

Introduction

The Adirondack Park is to some, an amazing feat of environmental conservation. To others, it is a forcing of tourism on a region that originally thrived on industrialism. To few, it is a place of colonialism; a global phenomenon linked to guilt, fear, and myth. The Adirondacks finds itself in this larger narrative of conquering, destroying, and removing. Euro-American perspectives on the region’s history have little room for non-White stories and landscapes. This has emerged from a lack of thorough research combined with the continued misuse of Indian[1]-inspired iconography. Insignificant are Indians in American heritage narratives. Moreover, in many parts of the United States, land seems to have been always in the hands of white settlers; land was something owned, by purchase, from another white landowner. However, this is not the case.

This thesis will ask two central questions to research this cultural heritage phenomenon. The first seeks to understand ownership of heritage narratives: What is the public perception of Native American presence and influence in the Adirondack Park, compared to representation in relevant literature? The second question is based in exploring wider heritage definitions: How do we expand and educate accurately the public of Native American heritage in the Adirondacks? These two research questions will be answered through an evaluation of relevant sources in the Literature Review, and in analyzing ethnographic data gathered during fieldwork at Santanoni.

The construction of the research direction began from a name, Santanoni. Santanoni is a peak in the Adirondack Mountain Range, located in Northern New York State. It also is the name of a nature preserve located in Newcomb, New York, which is operated by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). On the preserve there is an Adirondack Great Camp that bears the name of the peak. It is the place I spent the summer of 2017 exploring and preserving. Yet, more importantly, it became a symbol for the miseducation of Native American heritage in the region, and thus my interest in researching the topic further. Working as a historical landmark tour guide, I met and spoke with visitors daily, engaging them in the history of the region. When I was not engaging tourists, I was working on the preservation of the physical buildings of the site. I was given the opportunity to see preservation from various perspectives. Furthermore, I realized the role I played in giving people a narrative of heritage in the Adirondacks. I made a point to discuss Native American heritage in the region because it became obvious few did.

[1] The use of the names Indian and Native American will both appear throughout the thesis. In consulting living Indians, they tell me that is what they usually call themselves (Indian). In reading academic literature, Native American is predominantly used. In the book, A History of Native American Land Rights in Upstate New York, author Cindy Amrhein address the reader in explaining the book’s use of the title, Indian. She says, people she spoke with of Native ancestry, want to be called Indian because that is what is written in land treaties. She interprets this as a fear of losing rights if being referred to an identity not on the treaties (Amrhein 2016, 2). In the end, I decided to use both Native American and Indian on the precedent that I also use both White and Euro-American when referring to Caucasian settlers in the United States. The idea here is to talk about the two groups on equal terms, using both ‘politically correct’ and more colloquial but non-offensive titles of reference in the discussion.

|

Fig.2.1 |

An Adirondack Great Camp is a structure referring to large, private estates built by wealthy businessmen and socialites in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Santanoni, as I would tell visitors who came for a tour of the 16,000 square foot Main House, was part of a larger trend at the time of retreating to natural landscapes. Robert Pruyn was the original proprietor of Camp Santanoni, a successful banker from Albany who made his money as Director of National Commercial Bank, now called Key Bank.

|

Fig. 2.2 |

Interestingly, Pruyn considered himself a conservator of the environment and over the course of approximately twenty years, he accumulated 12,900 acres of land. This property included several small ponds and streams, three smaller mountains, a lake (Newcomb Lake), and the once public logging and mining road. His purchase of the land came from the ideal of privacy in having a gentleman’s estate, but also in blocking off the land from industrial development. By preventing mining and logging on large scales, Pruyn believed he was part of a larger cause in the 1880s and 1890s in the Adirondacks, to let the forest go back to its’ natural state, a state of ‘wilderness.’

|

Fig.2.3 |

Yet, what many may overlook, is that in forming this Adirondack precedent, there is an assumption that before European settlement and development, the land was uninhabited and a place of pure wildness. So how does the story of Santanoni and the Adirondack region provoke a challenge to the Western dominated heritage narrative? It started with investigating its origins. Santanoni is one of the many names that stands out in the Adirondack Park. Some names of mountains and towns come from Euro-American namesakes, or clear Americanization of Indian terms and titles. However, among the names, there are some with less clear origins. The name Adirondack is believed to be the Iroquois word for Algonquians, translated as ‘bark eater’. This has been popularized since the French and British began conquest of the Eastern seaboard, when the Algonquians sided with the French and the British formed alliance with the Iroquois, increasing conflict between the two and perhaps resulting in a derogatory name (Donaldson 1922, 35). If one consults Kanien’keha: An Open Source Endangered Language Initiative, an online resource of the Mohawk or Kanien’keha Nation, one can find the root word, ‘Ratiron:taks,’ which translates as ‘Algonquin people.’ [1]

[1] The literal meaning of the word is ‘They eat trees,’ but there are alternative spellings/pronunciations with their own definitions. ‘Rontsha’ka:nons’, ‘Atsha’ka:nons’, translate as ‘They gnaw on their lips,’ explained by the fact that the Algonquin language has m/p/b sounds while the Mohawk language does not. The other set of alternatives to Ratiron:taks is ‘Rontewa’ka:nons’ and ‘Atewaka:nons’ which translates as ‘They gnaw on their words’ (https://kanienkeha.net/people/other-peoples/ratirontaks/). Theories that do not include starvation and ‘savage’ Indians seem less enthralling to Americana culture however; consider that bark is used in natural medicine. Several types of trees local to the Adirondack Forest could be consumed including Birch and Cedar which can be used in teas to relieve pains and fevers and clean teeth.

While the name of the entire region ascribes Native American presence, their stories are rarely told or even acknowledged in Adirondack heritage today. The name Santanoni[1] continues this pattern; its origins are believed to be from an encounter between Abenaki (of the Algonquian) and French Catholic missionaries. Santanoni is said to be derived from the name of Italian saint, Anthony of Padua (In French: San Antoine, in Italian: Sant’Antonio). Santanoni embodies an Abenaki ‘corruption’ or mockery of the saint’s name Europeans called the region around the high peak (Engel et al. 2009, 34-35). The argument can be made for this theory based on the following factors: first, the Italian spelling and pronunciation of the Saint’s name, ‘Sant’Antonio,’ has an unquestionable similarity to its current name, Santanoni, second, if one listens to the Abenaki language, there is considerable pronunciation of the vowels sounds (The Adirondack Museum) and the way the name is said is by pronouncing all the vowels clearly, as in, san-tan-o-ni, and third,, mockery or disdain towards European missionaries by Indians would have been normal and expected.[2] As I began to work in the Adirondacks and learn these facts about the region, it confused and frustrated me that these ubiquitous pieces of history were not well researched or well known while the region’s environmental preservation is widely celebrated.

There are some more general patterns in American history that make the case study of the Adirondack Park an important one in expanding heritage representation. Fields & Fields (2014) identify that there has been what is called ‘racecraft’ in creating American culture, society, and economy. Race is a fabrication; it is a definition and belief created by Whites yet has no scientific basis in organizing human beings. Race has become something that is used and abused in organizing groups of people, linked in class inequality and cyclical poverty. Native Americans are not a separate race to Euro-Americans, they are different cultures or ethnicities; this idea of race has plagued American Indians like all non-Whites (Fields & Fields 2014, 265-266). Moreover, bias based on race has become subtler and harder to solve: “In racial disguise, inequality wears a surface camouflage that makes inequality in its most general form…that which marks and distorts every aspect of our social and political life—hard to see, harder to discuss, and nearly impossible to tackle” (Fields & Fields 2014, 268). The reasoning and continuation of American Indian invisibility represents the difficultly of solving race-based discrimination in all facets of American society.

One central facet is based in economies. The concept progress and civilization have become embedded in how American society views and understands Native American heritage. The belief that capitalism, development, and material possession equates to success and importance often acts as the basis for the argument that non-Western cultures are not meant to survive and sustain in what should be a Western-dominated world. All American high school students learn of Adam Smith and his capitalistic market theory of ‘the invisible hand,’ meant to represent the benefits of a self-regulated market economy of supply and demand. [3] Harkin (2012) utilizes Adam Smith’s historiography to argue that while Western society latched onto the progress of society and economy towards industry, materialism, and a further distancing from the ‘wild,’ Smith himself questioned the ultimate truth in such ideals. Harkin explains that Smith saw that assuming the ‘Age of Commerce’ as the final destination for the human race, claimed one way of living was superior without real challenge (Harkin 2002, 21-22). Communities that live off the land and in harmony with it do not fit this idea of progress. Harkin states that in analyzing Smith, one can identify his own curiosity in understanding the question: what is progress? (Harkin 2002, 29-30). As this thesis explores the need to rewrite the American historical narrative, questions including what is progress, success, and status will be asked of the reader in challenging Western cultural dominance.

There will be discussion in this thesis involving three main Native American communities. One group comes from the united tribes of Upstate New York known today as the Six Nations, commonly referred to as the Iroquois. [4] Their name in their own language means ‘they build a longhouse’ or ‘of the longhouse,’ written as Haudenosaunee. The Six Nations includes the Mohawk, Seneca, Oneida, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Tuscarora (Six Nations Museum). The nation of prime focus will be the Mohawk. Along with the Mohawk, this thesis will discuss Abenaki presence. Lastly, there will be discourse of the Mohicans of the Eastern Algonquians, specifically of the Delaware Nation (Tom Lake, Lecture ESF). The Mohawk, Abenaki, and Mohican have appeared in archeological surveys, family lineages, primary sources, and natural history amongst other sources, which led to identifying their place in the narrative of Adirondack heritage.

The main argument this thesis seeks to discuss is that without American Indian presence, the region would lack much of its influence and roots in shaping the celebrated Adirondack culture. This thesis does not wish to celebrate Indian heritage as only a part of history, but also recognize how their culture(s) helps shape the identity of the Adirondacks today. The central point of the thesis’s argument is thus that this phenomenon receives little attention in heritage representation locally and nationally, creating a dominant and dominated cultural divide in American society (Bourdieu 1989, 17).

The structure of the thesis will therefore follow as such: Chapter Two will review sources which claim information on the Adirondacks, the American Indian in American culture, and how the two contrasting topics reveal data towards the need to increase education and political voice of Native Americans in heritage preservation. Chapter Three will provide the methodology utilized in the fieldwork conducted. Chapters Four and Five will seek to engage with the fieldwork conducted in conjunction with the Literature. Chapter Six will conclude what the research and literature has presented regarding the main issues located and set to resolve. Additionally, the conclusion will include a cultural dominance continuum; the diagram will be an accumulation of data from relevant literature and fieldwork. The continuum demonstrates clear patterns in how non-white cultural heritage is trapped in a cycle of substandard representation and respect. The continuum thus offers answers to the research questions as well as possible solutions to the thesis’s main argument.

Consequently, the focus of this thesis and its structure is based in the recognition that one cannot talk about and work towards the preservation of cultural heritage without being conscious of and inspired by, the social justice aspects of such initiatives. Social justice, for the purpose of this thesis, is based in the realm of heritage. In this context, a community or culture that receives less representation, funding, recognition, etc. than another community or culture is more likely to be understood and treated unequally in a country’s economy, politics, and society than the cultures better represented, funded, recognized. Thus, equalizing heritage dominance in the United States can be seen as social justice initiative in several ways.

Robert Duffy (2016) writes of a Professor of Historic Preservation, Max Page, who is advocating for a deeper perspective on preserving and representing history: “…His [Page’s] conviction [is] that social justice considerations be included in official thinking about historic preservation – preservation not only of our silent past but of our vocal and distressing present” (Duffy 2016, Web). To Page, we cannot separate history from its people, and the stories not being told of the past reflect issues afflicting such communities today. Duffy goes on to quote Page, who stated, “The preservation movement…should be toward building a more just society” (Duffy 2016, Web). In studying the Adirondacks, Page’s convictions shine through in studying Native American heritage’s underrepresentation and miseducation across the state of New York. It thus becomes our duty to study and educate of the histories less told. This thesis could explore so much further and deeper, but as there are time and space limitations, the goal of the research questions to identify the main issue(s), consider the variables behind it, and provoke the status quo in promoting possible solution.

Chapter Two

Literature Review

This Literature Review seeks to consider the current scholarly literature accessible to the interested reader. Perspectives are from anthropologists, historians, environmentalists, archaeologists, journalists, and figures both White and Indian, broken into three sub-topics of discussion. The first topic, “Native American Invisibility in the Adirondacks,” focuses solely on the region of the thesis’s case study. The Literature Review will then move on to broader themes with which the Adirondacks intersects. The second topic, “Stereotyping & Appropriation: The Noble Savage,” considers the selective adoption of Native American culture and belief systems in creating myths of Indian presence and significance. The third topic, “What is Heritage: Different Forms of Preservation,” reflects upon the previous topics in light of the issue of recognizing and protecting non-Western heritage in the United States. These themes highlight the ways in which American Indians have gone underrepresented in the Adirondacks, beckoning systems larger than the region in the continuation of a Western dominated historical narrative. Each section will offer both academic and non-academic literature pertinent to identifying and examining the factors of cultural dominance in heritage representation.

2.1 Native American Invisibility in the Adirondacks

How scholars have approached writing surrounding Native American presence in the Adirondacks is varied to some degree, but often falls into the category of under-researched and over-stated. Most scholarly sources one can find about the ‘complete’ history of the Adirondacks glaze over briefly the topic of Native American presence. However, others take the time to delve deeper and look through historical documents, artifacts, and folklore in understanding the Adirondacks’ first dwellers. While the list of documents accurately informing readers of indigenous history is slim, those available do allow much needed insight on the topic. Reviewed below is a select group of sources. What is interesting to consider is each author’s interpretation and presentation of the past.

Underlying the discussion of Native American invisibility in the Adirondacks is a theory from French scholar, Pierre Bourdieu (1989). Bourdieu (1989) argues that power is socially and culturally recreated in ways that may mask themselves as natural but are far from it. This hierarchy, according to Bourdieu, is symbolic to primitive but also economic, cultural, and politic controls on a given society (Bourdieu 1989, 16-18). The symbolic power in a social space is normalized through a word used often by Bourdieu: habitus. The sociological terms states that (in the context of Bourdieu’s argument) power constructs become embedded in individuals and communities, presenting themselves as natural and even static. Bourdieu discusses the issue of repeatedly creating societies who have a “vision of divisions” (Bourdieu 1989, 17). Bourdieu’s theories on power and how it masks itself hold important truth to considering the Adirondack Park.

Specifically, Bourdieu’s commentary on how societies come to have a ‘vision of divisions’ begs the historian to ask how this shapes heritage representation. Creating a dominant and dominated culture, how much room is there really for American Indian heritage in the Adirondack cultural heritage from a historically White perspective? How power manifests, is not simply in the economy, government, and cultural tastes. One may argue, it also affects how the history of a nation is told; even in claiming how a nation’s cultural identity was formed. Therefore, there must be creative methods of uncovering a larger picture of the past in places like the Adirondacks.

To understand Indian influence and presence throughout the history of the Adirondack region, European land acquisition can offer significant evidence. However, while New York was one of the first North American areas colonized by Europeans, the Adirondacks remained absent from land purchase documentation. This has made it considerably more difficult to locate previous inhabitants in the vast region of Upstate New York.[5] Cindy Amrhein (2016) seeks to explore the history of land treaties, bribery, and manipulation of the law in New York State.[6] She analyzes the vital treaties[7] which altered Indian land in New York in the nineteenth century specifically. Her writing is well researched and there is clear consultation with Indians from the communities she writes about. However, Amrhein stays close to known treaties and disputes. This disallows research that is truly cumulative, specifically concerning the Adirondack Park region of Upstate New York; she glazes over a six-million-acre region while solely Franklin County’s Native population is discussed. [8] Amrhein’s research limits reveal a larger trend in misallocating pre-European presence in less documented regions like the Adirondacks.

Alfred L. Donaldson (1922) offers more detail in Adirondack land purchases.[9] Donaldson identifies central land purchases which formed the Adirondack Park overtime. There appear to have been two main purchases, one which was lacking from analysis in Amrhein (2016), the Totten and Crossfield Purchase.[10] Homesteading in the Adirondacks began in the eighteenth century, allowing more interest, maps, and records starting at this time.[11] Donaldson states: “The error is often made of assuming that this low price was the ultimate cost to the buyers, but it was merely what it cost to get the land away from the Indians-to get it away from his sacred Majesty was a much more expensive matter” (Donaldson 1922, 55). Earlier in Adirondack historical narrative, Donaldson presents there was the concept that the Adirondack region was in some sense of ownership by Indian nations and that it was purchased from Indians by Whites prior to the outbreak of war in 1766.[12] In considering the evidence Donaldson offers, there is still considerable knowledge missing prior to White land purchase. There seems to have been Indian ownership, but the outbreak of war, and sale from Indians to the British Crown (later, U.S. government) to American business men, creates a difficult trace to follow, one which Donaldson does not explore beyond European roles.

Karl Jacoby (2014) identifies Native American residents early on in Adirondack modern history while challenging the idealization of the region’s environmental movement. His ethnographic and social research is found in objects, photographs and stories, along with standard forms of scholarly literature. He states that legislation to conserve the Adirondacks, which had been nearly cleared by industry, began in 1885 in an alliance between academics and business owners[13] within the State of New York. He claims this mission of environmental protection had ulterior motives based in classism and racism.[14] Jacoby argues the creation of the Forest Preserve exaggerated ecological changes[15] in keeping the land from blue-collared business in order for laws pass faster (Jacoby 2014, 25).[16]

Jacoby uses census records[17] to locate both working class White and Indian residents in the Park. He reveals that the two groups followed a sustenance much closer to hunting and gathering of local wildlife and plants (Jacoby 2014, 23-24). Native Americans can thus be studied as having similar livelihoods and diet of White lower class families in the 1800s in the Adirondacks. A testament to the fusion of cultures, European and Indian, can also be observed in Adirondack material culture.[18] Jacoby presents a narrative which allows one to consider the fact that there most certainly were Native Americans in the region as it became one of the first natural parks in the world.

Melissa Otis (2014) extends the exploration of Indians in white settlement periods. Otis (2014) proposes that Native Americans of Mohawk and Abenaki descent including the Odanak were not only present at and before European contact, but as the American culture was forming in the 1800s and 1900s. She states, “Although there is no proof of permanent, year-round village settlement in the region, there is a plethora of evidence of their seasonal occupation on a year-round basis as well as cultural ties, including stories and burial sites” (Otis 2014, 556-557). Otis points to the fact that Indian presence in the region is not based solely on remains, but in the culture behind them in known oral traditions and sacred places.

Referencing Jacoby (2014), Otis deduces that the Adirondack region, before colonial hostilities and violence, had been recognized as Iroquois territory. When the Revolutionary War came to a close in the early 1780s, some Mohawk, Abenaki, and Odanak (St. Francis) settled with their families in the Adirondack region, living on homesteads year-round (Otis 2014, 557). After the Revolutionary War, Euro-Americans began to move in for industry jobs.[19] Along with white settlers, Indians began moving into the Adirondacks, living in villages and towns and partaking in the forming of Adirondack heritage. Otis explains that as tourism in the Adirondacks increased greatly by the late 1800s, wealthy families would hire guides with experience in the landscape for exploration purposes; many Native Americans took these jobs as they were the most knowledgeable. Otis presents this part of history as less told but vital in understanding a more holistic narrative.

Unfortunately, similar scholarly narratives often leave out the research and recognition of Indian culture and inhabitants. Philip G. Terrie (1994) offers a declaration of minimal significance of pre-European connection to the region. Terrie was curator of the respected Adirondack Museum on Blue Mountain Lake for many years and was well known as a scholar of Adirondack History. His book of Adirondack cultural history can be found almost everywhere in the Adirondacks. However, his presentation of a pre-European Adirondacks aids in widespread miseducation about Native Americans in the Adirondacks. Terrie creates the allusion of a wild Adirondacks that Europeans found in pristine, untouched condition. When referring to his sources regarding Indian presence, they appear almost non-existent; in the Notes section, Terrie references only three sources[20], all of which are outdated.[21]

A book by Terrie, published just three years later, claims to present a change in the scholar’s perspectives on Adirondack history. Terrie (1997) admits that his own work has been narrow and elitist (Terrie 1997, xv). The scholar discusses the fact that books on the history of the Adirondacks are often too focused on the politics of the upper class and the romanticized landscape, without truly engaging the reader in a complete historical narrative (Terrie 1997, xv-xvi). Contrary to Terrie (1994), he has more to say in 1997 regarding Native Americans but deduces that we have lost their connection to the region.[22] He writes, “It is a shame that we do not have the Mohawk and Algonquin stories...” (Terrie 1997, xviii). Terrie does not consider other means of research like archeology or oral history in uncovering Native nations’ perspectives.

Terrie decides to instead focus on conflicts of class and the Adirondacks, a reoccurring historical theme.[23] Terrie makes no real strides in his 1997 book beyond recognizing indigenous existence more truthfully: “The earliest stories about the Adirondack landscape were undoubtedly told by Native Americans—hunters, warriors, or traders…But what the Adirondacks as a place meant to these people has not survived…” (Terrie 1997, 3). Terrie assumes there are no stories yet here is no provided research or consultation with living Native Americans in the region (Terrie 1997, 3-5).[24] There is a constant assumption that the climate, lifestyles, and warfare reveal minimal Indian presence throughout history.

Paul Schneider (1998) also seeks to tell the tale of Adirondack landscape and environmental conservation, yet falls into similar ethnic biases shared by Terrie. Schneider provides a primary chapter touching on Native presence to set the stage for the Euro-American historical narrative. He includes a primary source written in 1609 stating that Natives came onto a Dutch ship.[25] Schneider assumes this group of American Indians were most likely Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), specifically Mohawk (Schneider 1998, 15-16).[26] While Schneider locates Mohawk presence, he discredits significant heritage of Abenaki (Algonquian) Indians. Schneider offers readers the idea that lowlands surrounding the region would have been more suitable for Indians (Schneider 1998, 16). Here again we see this commonly held belief in how the landscape would have been used yet Schneider, like others, does not have a background in evolutionary biology, archeology, or natural science. His sources are varied, some from primary accounts and some more academic sources and his conclusions are simplistic, allowing little insight (Schneider 1998, 337).

Kevin Sheets and Randi Storch (2016) adopt a similar narrative in their article when discussing the significance of the Adirondacks in U.S. history. Writing from the Cortland State College, their interest is in bringing to light the importance of the Adirondacks in larger historical events at the time. Sheets and Storch identify that when studying the Gilded or Golden Age of Industry to the Progressive Era and World War I, there is often little to no mention of the Adirondacks, which during this time period, was a region forming one of the world’s first public environmental conservation parks (Sheets & Storch 2016, 1).[27] They write, “Except to those Mohawk, Iroquoian, and Algonquian-speaking communities who used the region seasonally for hunting, the Adirondacks remained a blank spot on the map” (Sheet & Storch 2016, 1). This statement is eminent of oversimplified history. Furthermore, it suggests that if it was not known or used by Euro-Americans, it was not a place of significant cultural heritage before white man’s arrival. It is interesting to consider that Sheets and Storch identify the lack of literature on the Adirondacks but do not seem to realize their exclusion of pre-European inhabitants’ heritage.

Russell M.L. Carson (1928) offers more evidence of Indian presence by discussing the history of namesakes and famous individuals in the forming of the Adirondacks. In locating Indian presence in the region, Carson quotes Professor Emmons who recorded in 1834: “The Adirondacks or Algonquians in early times held all the country north of the Mohawk, west of the Champlain, south of Lower Canada, and east of the St. Lawrence River, west of the Champlain, south of Lower Canada, and east of the St. Lawrence River” (Carson 1928, 9). Carson presents the Eastern Adirondack region as Algonquin territory and that there was conflict for the region Emmons calls the Agoneseah, an alternate spelling of the Haudenosaunee or Iroquois (Six Nations). Carson agrees with Emmons in writing, “...It is well known that the Adirondacks resided in and occupied a part of this northern section of the state…” (Carson 1928, 9). It is interesting to consider his openness to the concept of Indian presence, writing in the 1920s compared to publications of Terrie and Schneider of modern times.

However, contemporary writer Stephen B. Sulavik (2005) discusses Algonquin and Iroquois history in the Adirondacks in significant detail, even if remaining focused on periods of European contact[28] (Sulavik 2005, 1-16). Sulavik finds his data in primary sources: maps, journals, letters. Archeology and natural science was also consulted in presenting ideas. Sulavik locates two main communities in and around the Adirondack region before and during European occupation. The Iroquois would have been in the Adirondack region, argues Sulavik, specifically the Mohawk. The other main group identified is the Algonquin. Sulavik offers the reader direct migration and presence of American Indian communities in the Adirondack region, referencing respected scholars and sources (Sulavik 2005,13-20).[29]

The value of Sulavik’s publication is in his use of comprehensive sources to explain a more detailed account of the Adirondacks pre- European inhabitants.[30] While the focus is still on ‘recorded’ history in the Western frame of historiography, the lack of bias apparent in Sulavik’s writing and factual evidence invites a more holistic perspective. He does not repeat the over-stated theories perpetuating Indian invisibility. Sulavik demonstrates that the whole story is there, but research needs to be done with creative and careful methods.

Yet, scholars and the general public often need more tangible evidence to believe Indian heritage is in the Adirondack region; archeological remains can offer this.[31] David Starbuck (2014) has propelled the use of archeology in recording the presence of Native Americans in the Adirondack region. Starbuck (2014) identifies the Lake George Region of the Adirondack Park (the South-West corner) to have been inhabited by Indians for thousands of years. Starbuck writes that archeological evidence first unearthed in the 1950s would have been most likely of the Mohican nations.[32] The archaeological remains located Indians as early as 8000 to 6000 BCE, in and around the Adirondack region. Pottery shards, projectile points, tools, and blades reveal considerable Native American settlement (Starbuck 2014,11-13). Starbuck remarks that the remains found back in the mid-nineteenth century, as well as his digs (in 2011 to 2012) include rich collections of prehistoric artifacts.[33] The evidence recorded provides concrete evidence of Native American presence, but it was found through the interest and resources of studying the Revolutionary War. The minimal archeological research in the Adirondacks can be attributed to a variety of factors. However, the fact that Euro-Americans are willing to fund digs for Western culture more often has no doubt dictated the historical narrative.[34]

The New York State Museum at Albany has one of the largest collections of archeological artifacts from the Adirondack region. They have been digitally cataloging the artifacts by each of the ten counties included in the Park. Anthropology Collections Manager, Andrea Lain, allowed me to view the full list of all sixty pre-historic, pre-contact, and historic (during or after contact) sites. While Lain explains some sites only border and are not all distinctly within the Park, the fact that they found multiple sites eligible for National Register Listing[35] sferred into visual measurement.nsaredacksrime example of ulated: iseducation, oversimplification, and policy. offers indisputable evidence of Indian presence and use of the landscape.[36] Knowledge or public awareness of archeological surveys and discoveries is still traditionally kept in the world of anthropologists, archeologists, and their connected universities and museums.[37] Yet considering the State Museum’s collection, discussing the findings of Indian presence more openly could offer much in expanding their narrative in the region.[38]

Lynn Woods (1994) offers a thorough account of the history of Indian presence in the Adirondack region. Woods (1994) uses archeology and natural science to trace the locations and connections made by Native Americans thousands of years before European settlement as well as during contact periods.[39] She states that while hunting settlements may not have been year round homes for American Indians, they no doubt would have formulated cultural ties to the region, even becoming part of folklore and ceremonial rituals (Woods 1994, Web). Moreover, Woods argues that there is ample evidence to promote this information more widely in the Adirondacks, “The presence of Native Americans in the region in relatively recent times is…an untold tale…The culture of … guideboats, lumber camps, mines, Great Camps…is a mere sliver in the mile-long slice of time representing Indian occupation” (Woods 1994, Web). Woods attributes this misinformation to the lack of guaranteed findings swaying some archeologists away from surveying the region, compared to other well established areas. She also presents the idea that a portion of Indian settlement was along water ways which have shifted considerably due to man made dams and natural causes. Additionally, Woods states that frequently Indian ‘relics’ or remains have been kept privately, stolen, or destroyed.[40] These aspects have aided in the dismissal of considerable influence and presence of Native Americans in the region.[41]

Curt Stager (2017) combats traditional ideas about the Adirondack Region[42] by using his knowledge of the environment. Stager is a natural science professor at the local university, Paul Smith’s College. Stager is not an anthropologist or archeologist, but his knowledge of natural science history led him to explore the region’s original inhabitants. Considering two ice ages which occurred in Upstate New York, Stager argues the Adirondacks would have been very much habitable for Native Americans, specifically in the Late Archaic period. He relates such ideas to archeological remains.[43] Stager is not only interested in relevant evidence of Indian presence in the Adirondacks, but also in interpreting why the general public disregards such history.[44]

Stager points to recent finds and continued excavation which has expanded upon Wood’s article.[45] Stager argues the lack of Indians in the region today add to the Western dominance of recalling past; he blames disease and war for killing off a majority of such communities during European contact. By the time written records were being produced, few Indians were still living in the mountains, making it seem the land was simply for the Euro-American’s taking and that previous native settlement was a myth (Stager 2017, 60-61). Stager writes, “The blending of people and wilderness in the Adirondacks was not invented with the establishment of hotels, colleges or the Blue Line.[46] It is thousands of years old…” (Stager 2017, 62). For Stager, it is a fairly new revelation that the heritage taught and celebrated in the Adirondacks tells a specific story, namely a White one. However, it is never too late to change this supremacy.

Non-Academic Literature

Regional folklore is vital in understanding cultural history and its perceptions today. The following two sources offer non-academic perspectives to examine the literature topic. The use of legend and lore in understanding Native presence can be studied in a publication from the the 1930s. Eleanor Early (1939) presents a collection of stories, both fiction and nonfiction, which involve the Adirondack region. One story entitled, “The Holy Savage,” follows Father Jogues[47] in his attempt to convert ‘heathen’ Indians around Lake George; the Indians in the tale are almost always identified as Iroquois (Early 1939,119-121).[48] Another legend tells the Saranac Indians’ story of the birth of the water lily (Early 1939, 147). This tale places Saranac Indians in the region as well as presenting Native connection to the landscape, specifically in the Saranac Lake region. [49]

Early describes what the Adirondacks would have been like before Whites, writing “Men used to call them the Great North Woods, and they were filled with moose and wolves...There were Indians too, but they were mostly good natured” (Early 1939, 5). She tells the story of a simple wilderness, and although she is demeaning Indians, it does include them in the spatial orientation of the Adirondacks. Early’s inclusion of Indian namesakes and legends places them in the region as well as being capable of forming a sense of cultural connection to the mountainous landscape.[50] In regards to the fifth tallest peak in the Adirondacks, Whiteface Mt, she declared that another community had its own name: “The Iroquois Indians called the mountain [Whiteface] ‘Theanoquen,’ which was the name of a great war chief who had a white scalplock. And the Algonquians called it “Wahopartenie,” … ‘it is white’ (Early 1939, 158). Whether they are completely credible or more folk tale, these legends’ existence expands the narrative, challenging the belief that Native American were hardly present and if they were, it was long before the White man.

Don Bowman (1993) reflects upon Native American heritage from a Native American perspective, telling stories that are not all ancient in origin and mixing stories from the 19th and 20th centuries with traditional tales. The Sacandaga Valley, as explained in his book, was flooded by one of the many dams built in the Adirondacks waterways in the 20th century (Bowman 1993, xiii). The Sacandaga Valley is now Great Sacandaga Lake or Reservoir and lies along the Southwest section of the Adirondack Park. Contemplating the literature previously discussing Native American presence in the Adirondacks, few scholars connect to any modern presence of Indian communities in history, save for the work of Melissa Otis (2015) and Karl Jacoby (2014).

The dam that was built reveals a Native American community’s rooted existence within the Adirondack Park: “When notices that the valley was to be flooded…Sacandaga Valley memories and claims and kin stretched five and more generations in one familiar place” (Bowman 1993, xiv).[51] (Bowman 1993, xv). The stories vary in subject, telling tales of the forming of the lily pad and seeking out a shaman on a mountain to stop a great forest fire, to more recent stories of Sacandaga townspeople. They reflect cultural connection to the landscape in its most authentic form: an attachment to a place and its people (Bowman 1993, 1-40). Not dismissing the significance of ancient settlement, the modernity of certain stories aids in a more viable connection to expanding the ‘American’ hold on the region’s heritage representation. Perhaps, this can create a deeper understanding of Indian influence and presence in the region, beyond what Euro-Americans claim their history was and is.

2.2 Stereotyping & Appropriation: The Noble Savage

Cultural appropriation is something that occurs everyday. Yet when it is carried out in a way that degrades and objectifies a community, it is harmful on many levels. Furthermore, it presents the idea that a culture has disappeared, allowing its use and even its manipulation. In shaping the outdoorsman, the Adirondacks borrowed much from its Native American communities, despite the general belief that they were never permanently in the region and not of significant impact. The irony of such perception represents issues which occur elsewhere in the United States. This section of the literature review seeks to address Indian stereotypes from various points of view. The main manipulation of Indian identity to be discussed is the figure of the ‘Noble Savage.’ The Noble Savage is the accumulation of two hundred years of serotyping; a non-threatening, child-like, godless yet simple and earth loving entity, equated more to a fabrication of reality than a human being. The use of such imagery understates the bigotry towards Indians and remains a key variable in understanding the prominence of the belief that they are no longer present. Furthermore, it assists in explaining public perception of Indian impact and historical placement in American cultural heritage.

Like any lasting stereotype, there is some truth and some myth to the framework grouping a diverse people into singular descriptions and characteristics. The Noble Savage blends positivity with negativity in its imagery of Indian communities, but one ideal reveals itself clearest: a sense of powerlessness. The most important aspect of the Noble Savage and the most decisive reason for its continuity is that it continues to subject Native Americans to the placement of second-class citizens. Nevertheless, scholars have argued for and against this idea of living close to the Earth when depicting Indians in the United States. This section seeks to engage in such dialogue with the goal of understanding the stereotype and its role in the case study of the Adirondack Park.

Christopher Vecsey and Robert W. Venables (1980) seek to evaluate the effect of stereotyping on Native Americans and their representation in the past and present. They write, “Since white America’s wealth has come directly from the taking of Indian land, whites have been willing to espouse an ideology in which Indians have been made inanimate…” (Vecsey & Venables 1980, 36). This frame of thinking, argues Vecsey & Venables, allowed white settlers and businessmen to justify domination of both Indians and the landscapes[52] they developed spiritual closeness to. Euro-American culture considered this lifestyle less civilized and vastly inferior[53] However, the book identifies, like any community, respect for land was only one segment of Native American culture. Vecsey & Venable write the Iroquois “…Believe that the survival of their culture is tied to their land and their ability to control that and through an exertion of sovereignty” (Vecsey & Venables 1980, 82). Reflecting on Iroquois presence in the Adirondacks, the critical ideal argued (an ideal characteristic of any organized community), is that there cultural connection to the landscape is vital in maintaining a sense of self-determination and sustainability.

Oren Lyons, chief of the Onondaga Nation, Iroquois, offers his own perspective in Vecsey & Venables (1980), explaining that his community, like any other, only wishes for respect in the form of true sovereignty. Lyons explains that their central belief remains that all living things are equal. He urges the reader not to just think about Indian rights but the rights of our Earth and the need for all to consider the ways we can serve the next generation (Vecsey & Venables 1980, 173-174). Real sovereignty is not readily found in the stereotype of the Noble Savage as it would equate white man with Indian, thus humanizing American Indians.

Shepard Krech III (1999) seeks to engage with the stereotype of Noble Savage in noteworthy contrast to Vecsey & Venables (1980). Krech argues Native Americans modified their environments just like any community, using intelligent design to utilize the earth for their own growth and survival (Krech III 1999, 9). Krech states the time period of 1875 to 1940 as critical in forming the Noble Indian stereotype in printed form, attracting mass attention and influence (Krech III 1999, 19). Krech identifies certain key figures in the movement, including author of historical fiction novel, Last of the Mohicans, James Fennimore Cooper, as well as Ernest Thompson Seton, first Chief Scout of the Boy Scouts, and Charles Eastman (Ohiyesa) who was part Dakota and part Sioux. [54]

Krech’s insight in the counter argument to Noble Indians as ecologists is useful[55], as it allows another side in the dialogue, straying away from looking at Native Americans as victims. Krech’s research is extensive[56] and his points are not overtly biased upon reading, however, Krech does lack any real basis in Indian cultures. While touching on the ideas surrounding religion and land, he does not truly explore them in terms of environmental use and sustainability. Furthermore, in the way Krech writes, there is an uncomfortable sense of antagonism; there seems to be a double standard that Indians can either be wasteful and ignorant to ecological preservation or are aware of it and seek to manipulate and profit from it. Krech misses the point that this idealism of the Noble Indian often makes Native Americans seem simple and their culture underdeveloped (the savage part of the stereotype of Noble Savage) (Krech III 1999, 115-217).[57]

Shari M. Huhndorf (2001) offers an examination of the Noble Savage, this time from the way Americans intersected with Indians, not how Indians intersected with Americans. Her interests lie in investigating literature, material culture, and larger social practices that have appropriated and dismantled American Indian heritage in forming a solely ‘American’ one.[58] Huhndorf writes that literature discussing this trend has been minimal, “…Because much scholarship in the field tends to view Native America in isolation from the dominant, colonizing culture” (Huhndorf 2001, 6). In forming the American identity, the frictions between democracy and racial hierarchy have left out stories of conquest and violence (Huhndorf 2001, 11). Native Americans, being the first to experience colonialism in the New World, have been excluded from the narrative, instead made into figures unrealistic but almost always beneficial to the legacy of the United States.

Similar to Krech III (1999), Huhndorf discusses the growth of the Boy Scouts and other men’s clubs at a time when there was a desire to maintain masculinity in a rapidly changing industrial society seeking to grow its imperial might. She writes that the Boy Scouts came after a handful of already established organizations.[59] The late nineteenth century was a place of urban chaos, revealing itself through poverty, disease, crime, and deplorable labor laws (Huhndorf 2001, 67). Huhndorf argues this added pressure to continue racial segregation: “The nature of modern life, no longer seemed clearly to demonstrate the superiority of the white race. To explain and justify their dominance, European Americans had to look elsewhere” (Huhndorf 2001, 67). By the time the Boy Scouts arrived from England to the U.S. in 1910, the appropriation of Indian cultural heritage was in full effect.[60] Huhndorf asks the reader why an organization based in white male Protestant values with imperialism desires would utilize Indian cultural inspiration. Huhndorf analyzes that by exploiting Indian based ideals, the Boy Scouts “…Conquered but emulated them as well” (Huhndorf 2001, 72). Huhndorf explains that through this ‘emulation,’ young American boys were reenacting idealized stages of Western progress to continue the idea of white supremacy.

Indian-inspired clothing, names, and outdoors skills became more broadly utilized in American summer camps and organizations. Susan Miller (2006) compares and contrasts two books, A Paradise for Boys and Girls: Children’s Camps in the Adirondacks by Hallie E. Bond, Joan Jacobs Brumberg, and Leslie Paris and A Manufactured Wilderness: Summer Camps and the Shaping of American Youth, 1890-1960, by Abigail A. Van Slyck. Miller (2006) identifies that there has been minimal academic focus on summer and youth in the past. Miller states that Bond writes less from an analytical and more from a nostalgic point of view. Bond was curator of the Adirondack Museum when this book was published and was inspired from one of the exhibitions at the museum (Miller 2006, 96). Discussion of the influence by American Indian culture is left out of the conversation.

Miller writes that Van Slyck’s book however, uses cultural theory to assess the meaning behind the growth of summer camps in places like the Adirondacks.[61] Miller continues, stating, “… An examination of tents and tepees allows her to explore Americans’ fascination with giving their progeny ‘‘Indian’’ role models to emulate. Occasionally, this model forces a somewhat arbitrary distinction” (Miller 2006, 97).[62] Again we see the adoption of Indian culture for White American used, yet Miller seems to glaze over the importance of this detail. For Van Slyck, summer camps signify anxieties about class, race, gender, childhood, and health occurring at this point in American history. Van Slyck (2006) writes, “It is perhaps even more important to recognize the ways in which summer camps…served as incubators of the middle class, instilling middle-class values…” (Van Slyck 2006, xxxiv). She argues cultural identity was rooted in the growing interest of summer camps. Like Huhndorf (2001), she contextualizes her topic in the period of history (late 1800s to early 1900s) critical in shaping American cultural values in response to larger issues and concerns at hand. Fabricating a new generation of wholesome ‘American’ kids, Van Slyck argues these camps tell a larger story. Miller however, downplays the cultural critique of A Manufactured Wilderness in her article, offering a narrative closer to A Paradise, more interested in dwelling on the nostalgia.

Pauline Turner Strong (2008) articulates the ideas of Van Slyck and Huhndorf in her article centered the youth organization, Camp Fire. Strong states that Camp Fire became the first multiracial youth organization in the U.S. specifically for girls. Founded in 1910, the organization came at a time of shifting perspectives on everything from American anthropology and ethnography, namely in the efforts of scholars like Frank Boas, and in gender rights by becoming co-ed by the 1970s. Camp Fire shaped much of its programming around ‘Indian’ traditions, images, and rituals, believing it would emulate the cohesion and goals of the organization. Today known as Camp Fire USA, the organization still retains and celebrates these Indian-style characteristics like the Boy Scouts of America (Strong 2008, 1).

By the mid 1900s, the Noble Savage was due for a rebirth, this time within counterculture movements. With environmentalism underway in the U.S., the Noble Savage was considered the perfect figure to utilize in the cause for anti-pollution, anti-nuclear, anti-war, and hippie angst (Huhndorf 2001, 132-136). [63] However, there were American Indians interested in changing this perception of their culture as a malleable stereotype. As Americans continued to adopt Indian ideas for their own Euro-American needs, the American Indian Movement (AIM) was seeking its own place in the civil rights protests of the Vietnam War era. The joining together of students of several nations[64] offered a strong coalition of young American Indian activists. Alvin M. Josephy, Jr. (1971) as a White scholar. However, I include this text because the book is almost completely a collection of speeches by Indian leaders of the AIM.[65] In 1968, a speech by Sidney Mills was made, entitled “I Am a Yakima and Cherokee Indian, and a Man.” Mill’s speech is made in the attempt to humanize Indians, differing from Eastman’s language (1914). He writes: “What kind of government or society would spend millions of dollars to pick upon our bones, restore our ancestral life patterns, and protect our ancient remains…while at the same time eating upon the flesh of our living people with power processes that hate our existence?” (Josephy 1971, 96). This fascination with Indian culture both in grassroots counterculture and academic research acted as a strange juxtaposition to Indian rights.[66]

The sense of Western dominance is impossible to ignore, looking at Indian cultures as stereotypes to use and study, but rarely as humans. Mills demands Americans to consider Indian cultures as just like their own; worthy of the rights, opportunities, and platforms deserved of all U.S. citizens. It is confusing to consider the ideas of the American Indian Movement (AIM) in conjunction with the appropriation occurring during the 1960s and 1970s. While the AIM spoke of sovereignty, equal rights, and an end to the disappearance of their cultures and ways of life, White Americans were taking on the identities of Native Americans, interpreting their actions as a nod to their own goals of sustainability. Unsurprisingly, this trend accomplished the exact opposite.

Shirley L. Smith (2012) situates the counterculture movement with the AIM in pushing for increased political and economic self-determination. In this era of activism, Smith identifies that Native Americans were able to attain media spotlight during the 1960s and 1970s (Smith 2012, x.). Smith dedicates much of her book to the attention hippies gave to Native American culture through their appropriation of their clothing, styles, and relationship to the landscape. However, she also sheds light on how much of American counterculture manipulated elements and beliefs of a marginalized culture, therein embodying appropriation.[67]

The insult and hostility various Indian individuals and communities felt towards this take on their heritage is unsurprising (Smith 2012, 129-131).[68] Some took it with bemusement and would trick hippies, however, most saw this oversimplification and appropriation of their heritage as offensive and damaging in what Smith states was an ‘insensitivity’ to Native Americans (Smith 2012, 131) .[69] She writes of one Taos Pueblo teenager, Diane Reyna, who found the hippies interesting, unlike older generations. However, she too observed, “ ‘There was no way they could have any idea what it really meant to be Indians’ ” (Smith 2012, 133). Smith concludes youthful Americans’ adoption of Indian cultures remained superficial in an attempt to use another culture to combat one that was crumbling: their own.[70]

A similar trend can be seen in the location of the Thesis case study. Joe Connolly (2017) describes a group of college-aged students from the Upstate New York region who attempted to live off the land in the late 1970s near the town of Saranac Lake. Connolly writes: “In the corner...sits a 20-foot-high tepee frame…There are remnants of a meditation labyrinth and a medicine wheel garden… They considered themselves pioneers, wanting only to live cooperatively with the earth, to protect it and to never own it” (Connolly 2017, Web). This commune, The New Land Trust, called itself a tribe, utilizing Indian inspired cultural traditions, practices, and livelihoods for their own social statement. Connolly praises and celebrates the student’s use of simplified Indian culture without giving American Indians any real recognition in the narrative. This article reveals the continued dismal of living Indian culture and the respect they deserve.

Finis Dunaway (2008) also discusses the use of the idealized ecological Indian in the 1970s, this time with a focus on Earth Day.[71] Dunaway states that there was an indefinite appeal counter-culturists felt towards the ideals of Native Americans.[72] Dunaway points to visual platforms which were used to motivate and challenge environmental degradation in the United States (Dunaway 2008, 84-87). While showing images of student demonstrations and creating TV adverts, the use of Indian figures appeared as well. A fictional Indian, played by Italian-American actor, Iron Eyes, was placed on magazine ads and in a live action commercial paddling across a polluted waterway, shedding a tear of distress at the state of the environment for the 1971 “Keep America Beautiful” Campaign (Dunaway 2008, 84-85). Iron Eyes presents to the American masses that the Indian cannot survive in this world of chemicals, pollution, industry, and urbanism. This creates a fabricated culture simpler than Western society. While on the surface, the commercial may seem beneficial to this ecological Indian, this is a Western idealization which creates a sense of myth and inanimateness.

Robert F. Berkhofer (2011) sees this inanimateness as a trend through American history to create the ‘other’ in society (Berkhofer 2011, 6). He writes that no matter the stereotype, Native Americans are always shaped to be ‘alien’ to Whites (Berkhofer 2011, 6). The first definitions attributed to Indians were violent, heathen, and dangerous. Yet, the evolution of environmentalism with Indian cultural beliefs has just created different divides in America. Moreover, Berkhofer states that the people who were living in North America when Europeans arrived, had never really considered themselves a collective group or ethnicity; this was a European initiative which undervalued their diversity in dress, food, spirituality, architecture, etcetera (Berkhofer 2011, 14). While aware of these contentious foundations of American identity, Berkhofer points to modern understandings of Native Americans being rooted in the ethical archeological and ethnographical teachings of Frank Boas. Boas, considered one of the founders of American anthropology, coined the term ‘cultural relativism,’ which states that no one culture can be superior or inferior to the other[73] (Berkhofer 2011, 302). Yet even as Boas and others began to push such beliefs by the 1930s, the study of anthropology still perpetuated the idea of an ‘other,’ specifically an ‘other’ of the past.[74] Even though today, the ideas pushed by Boas seem common sense and necessary, he only died approximately eighty years ago.

Jack Weatherford (1992) seeks to dismantle the ‘other’ by referencing early European encounters and assessing the countless influences which helped shape American cultural identity, Weatherford argues there is intricate importance in recognizing these additions. Such influences[75] include hunting, beads, buildings, agriculture, fishing, the Americanization of the English language, names in the U.S., and environmentalism and peacekeeping (Weatherford 1992, 1). Weatherford states that, "Beneath the surface of . . . American accomplishments, lie indigenous roots" (Weatherford 1992, 2). Yet, this idea of acknowledging Indian influence remains difficult for institutions to admit, and even harder to promote to the masses. It comes back to this question of what is progress. It has long been considered that the West dominates the evolution of civilization. However, the growing need to consider other voices in accepting Indian influence becomes obvious here. Understanding how Native Americans added to the economy, to government[76], and subtler socio-cultural traits can allow a more accurate representation of the first ‘Americans’. Furthermore, it asks us to consider their rights and citizenship in a modern America.

In discussing the sources for this section of the literature review, it becomes apparent that stereotyping and appropriation are not simple terms to understand. They appear in strange places and can be extremely subtle or shockingly obvious. From the first European encounters in Colonial America to youth organizations and environmental activism and hippies, we see the manipulation and oversimplification of Native Americans. Indecency and insensitivity of stereotyping and appropriation can be readily recognized by the average American, or missed completely, allowing it to perpetuate in a dangerous cycle of miseducation.

Non-Academic Literature

For the reason that appropriation and stereotyping are part of American history, observing non-academic sources which offer insight into the origins of misrepresentation is indefinitely beneficial to the topic of research. As discussed by Krech III (1999), Charles Eastman was an American Indian but adopted Euro-American dress and was Ivy-school educated. An interesting figure to study, his writings compiled in the 1914 book, Indian Scout Talks: A Guide for Boy Scouts and Camp Fire Girls, shapes this image of the Noble Indian, knowledgeable of the environment, living off the Earth, and simple and wise in his ways.[77] Eastman’s motives may have come from a desire to paint a less savage and more peaceful Indian in the minds of American boys and girls. While the ideas and methods presented in Eastman’s book are not degrading, he helped create a stereotype of American Indians, as well as furthering the notion that Native American cultures were more of the past than the present.

The book targeted the Boy Scouts and the Camp Fire Girls, which both based much of their organizations’ Native American values and activities on the ideas of Eastman. The book is organized into chapters among topics including animal and plant knowledge, wilderness skills, and Indian spirituality and symbolism. The language is simplistic but to a questionable degree; it is always, “the Indian,” when discussing Native American beliefs and traditions, yet Eastman’s own personal experiences, family, and Indian nation(s) are being presented as hundreds of nations practices.[78] The Indian is every nation to the White reader, allowing Euro-Americans to group Indian nations of great diversity and heritage into a singular ideal. Moreover, the text can become problematic as the ‘Indian’ in Eastman’s book feels more like a fictional creature, presented as lacking power or status outside the ageless domain of nature.[79] This oversimplifying allows cultural appropriation to occur, shaping not only the public’s ideas but more decisive government and economy.

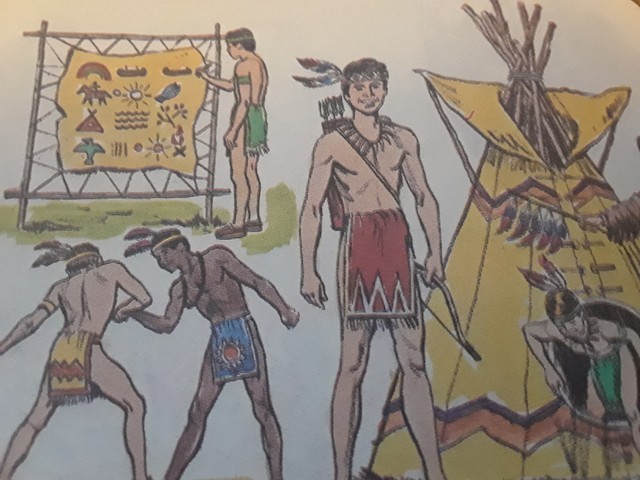

|

Fig. 2.4 (Hillcourt 1982,162)

|

To study the lasting effects of which Eastman lent to, a glance at Boy Scouts of America reveals much in the way of Native American stereotyping. The analysis of The Official Boy Scout Handbook: 1982 Edition, was conducted. In the “Primitive Camping” section of the handbook, the top of the page includes a series of illustration showing boys dressed in loin clothes, using bow and arrows, going out of tepees, painting on buck skin, and wearing feathers and moccasins. Underneath the images, it states, “In Indian-style camping you help keep alive the traditions of the earliest Americans. You learn to play Indian games and take part in Indian dances” (Hillcourt 1982, 162). This source reveals that the use of Indian inspired activities and dress perpetuated the idea that Indians were no longer alive and that Boy Scouts assumed the role of “keep[ing] alive” their culture (Hillcourt 1982, 162). The badge earned in partaking in ‘Indian-style’ camping or ‘survival-camping’ was called the Indian-Lore Badge. One can also partake in Pioneer Camping, which follows Primitive Camping, a metaphor for the ‘evolution’ of America.

[1] Russell M. Carson (1928) explains there are forty-six named peaks that measure over 4,000 feet in height. One such peak is Santanoni Mountain, at 4,606 ft. Carson states the first people on the mountain would have been French and Indian. The first known appearance of the name in print is in 1838 by a William C. Redfeld in the American Journal of Science and Arts (Carson 1928, 23). Professor Emmons, in 1842, calls it Saint Anthony, corrupted into the name Santanoni. The word Sinondowanne was used in the 1840s to 1870s, meaning “the great mountain.” In Seneca, Carson identifies the word to actually mean “great hill” though. Carson writes that Professor Arthur C. Parker, who is of Seneca and English/Scottish descent, explains the theory as such in the early 20th century (Carson 1928, 24). Parker states the name must have been used by an Adirondack Indian guide of the Abenaki Tribe, or possibly by a St. Regis Indian [Mohawk], whose Saint name would be the same as the Abenaki’ (Carson 1928, 24).” Here Carson refers to Franciscan missionaries bringing the name Saint Anthony of Padua (Carson 1928, 34)[1].

[2] As seen in the Catholic missions in California during Spanish conquest, there was often little choice for Native Americans facing invasion. Either they could adopt Christianity and live in mission villages, or face the definite possibility of death fighting it. However, those that did follow missionaries often found various subtle ways to undermine and rebel against forced European assimilation. To mock a Saint’s name would fit into this relationship during colonization of North America (Dyck 2016, University of Toronto Lecture).

[3] Smith’s theory became closely tied to Western imperialism and development for centuries to come.

[4] Iroquois as a title for the united nations, was originally used by the French.

[5] Interestingly, Amrhein writes that before 1790, New York actually included what today is Vermont (Amrhein 2016, 17). Vermont still has an identified Abenaki presence and it is important to consider earlier borders and forms of exchange based on them.

[6] Her book relates this research to present day issues regarding Indian land rights, specifically for the Iroquois nations who still remain on their original land.

[7] Amrhein shapes the book around several significant land acquisitions that occurred in the 1700s and 1800s mainly, with discussion of living tribal conflict over the injustice of these earlier ‘negotiations.’ One such treaty is the Macomb Purchase, which encompassed Franklin County, part of the Adirondack Park today. Alexander Macomb became wealthy during the Revolutionary War as a merchant and sought to spend his money in land speculation in Northern New York (Amrhein 2016, 29-31). Both St. Regis Mohawks and Caughnawaga Mohawks attempted to fight the purchase of their lands between 1792 and 1794 but New York State disregarded their claims as they were more interested in the Western New York land treaties occurring simultaneously with the Seneca Nation.

[8] While Franklin County, a county which is in the Park, is discussed in detail with regards to legal actions against one treaty, Macomb’s Purchase, the reader is missing study of a considerable part of what constitutes Upstate New York. Conflicts continue over this purchase in Franklin County where the St. Regis Reservation still stands today: “The St. Regis Indians were sure of what they owned and have long contended that some of these parcels were encroachments on their territory” (Amrhein 2016, 59). This text reveals Mohawks were long connected to Franklin County.

[9] There remain a few historic maps of the land purchases which encompass parts of the Adirondacks. A map drawn in 1886, entitled ‘Sketch Showing the Location of the Great Land Patents” (Donaldson 1922, 53) includes Macomb’s Purchase which incorporates Saranac Lake and Paul Smith’s. A Great Military Tract is also marked which included Lake Placid and Keene Valley. Totten & Crossfield’s Purchase includes Mt. Marcy, Long Lake, Newcomb, and Raquette Lake. Donaldson writes that “‘Before and during the colonial period it [the mountain hamlet of North Elba] was the summer home to Adirondack hunting bands. In all the old maps an Indian Village is located near the spot’” (Donaldson 1922, 35). North Elba is today located just South of Lake Placid in the Adirondack Park. Donaldson references scholar Winslow C. on possible settlement in North Elba. He states: “The vestiges of Indian occupation in North Elba, and the territory around the interior lakes…leave no doubt that at some former period they [the Indians] congregated there in great numbers” (Donaldson 1922, 27). This account offers some confidence in Native presence. H.P. Smith’s “Aboriginal Occupation of New York,” a bulletin of the New York State Museum, published in 1900, in describing North Elba, he merely quotes Watson: “There are no important sites in the county, but many traces of early and late passage. On early maps in the New York wilderness is called the hunting ground of the Five Nations, and it was their tradition that it had never been otherwise used” (Donaldson 1922, 28). This discussion about North Elba, reveals how myth begins in historical narrative. Nevertheless, the idea that the land was hunting grounds places Native Americans in the region.

[10] Totten and Crossfield were shipwrights working out of New York City. They had written to King George III prior to the Revolutionary War, with interest in buying land including part of what is today the Adirondack region. While their names continued to be placed on Upstate New York maps in the 1800s, after they passed, they may have not been the official owners of the tract, meaning they were merely considered as possible buyers in the sale of the land. Also seen on later maps is, ‘Jessup’s Totten and Crossfield Purchase, referring to the Jessup brothers and their son, who were intimate friends with important military leaders at the time including General William Tryon. The Jessup’s owned land in what is today Warren County, but their town burned in the Revolutionary War as they were known Loyalists (allied with the British) (Donaldson 1922, 50-52).

[11] As Donaldson states, “Before the Revolution the colonial government, and after it, the State, made larges sales of its “wild lands” in the Adirondack region” (Donaldson 1922, 51). Specifically, after the French and Indian War (1759), in the years prior to the Revolutionary War, southern parts of the Adirondacks along Lake George and more central, along the Central Hudson River were being moved in to with dying down of violence (Donaldson 1922, 52).

[12] Macomb’s Purchase’s first tract of land was acquired in possession in 1792 (Donaldson 1922, 63, 65).

[13] As big money from cities started coming to the Adirondacks for leisure and sport, interest grew in buying property and privatizing land. With money came the idea that one could afford to think about conservation in relation to one’s ownership of the land.

[14] Jacoby aligns this movement with the disassociation of the local community from their way of life. The criminals of the Adirondack Forest Preserve established at the end of the nineteenth century were rural farmers and hunters, and perhaps even more hidden, Native American locals including the Abenaki. He explains that conservationists presented lands like the Adirondacks, not as a homeland, but merely land being exploited for economic use.